Ίδρυση μιας ενεργειακής κοινότητας (στα αγγλικά)

With an established international consensus on the need to move away from fossil fuel-based energy sources and reduce emissions of CO2, more and more countries are making atransition to renewable sources of energy.

Along with the change from fossil fuels to cleaner renewable energy, also the possibility opens of a change from passive energy consumers, and a centralised energysystem to active prosumers and more local decentralised distribution systems stimulating local economies. The Energy transition presents a once in a generation opportunity for communities and countries to increase the prosperity and resilience of local economies. In this sense, decentralising the energy system through locally owned renewable energy presents “one of themost promising prospects for a healthy, social and economic development.”

As part of this global consensus of a transition to a low carbon economy, many governments are passing climate related legislation.

1. Why energy communities?

Renewable energy communities are grassroots initiatives that invest in ‘clean energy’ in order to meet consumption needs and environmental goals and thereby –often unwittingly –conduce to the spread of renewables.

Energy communities contributing to renewable energy production leads both to returning energy prices and investment and also fighting climate change.In its recently released Clean Energy Package, the European Commission finally acknowledged that energy communities –such as cooperatives –have a major role to play in the Europe’s energy transition.

This could be a potential game changer for people and communities across the EU. The European Commission has tabled its proposal to reform the EU’s electricity market and better promote the use of renewable energy sources.

Also, Energy democracy is important for the next reasons:

1. The cost of producing energy from RES is constantly decreasing and is already directly competitive with (subsidized) fossil fuels.

2. The democratization of the energy sector ensures that replacement of dirty sources to clean energy will be done in the fastest and socially fair way.

3. Many energy activities with enormous environmental and developmental benefits (eg biomass, biogas) remain on the sidelines due to lack of interest or bureaucratic obstacles. The institutional framework for energy communities facilitates their development.

1.1 The key actors of energy communities

The key actors/stakeholders of an energy community include:

• Energy citizens: Citizens have the opportunity to get informed and trained -in the framework of energy democracy – in the areas of energy saving and to the production of energy in their households and businesses.

• Civil society organizations: Local village groups, residents, associations, interest groups predominantly voluntary in nature are organizations with an existing structure and membership who may have an interest in getting involved in energy-related projects.

• Non-governmental organisations: These organizations can provide information, access and support.

• Government actors: Regional/Local authorities (the local mayor, the head of therelated department, an engaged employee) should be engaged as supporters and potential partners of the energy project.

• Government agencies and capacity building organisations: Government agencies that can provide support and information (The national department of energy, the department of social enterprise, the department of community development, other government agencies).

• Social Finance Organisations: Social finance organisations specialize in providing finance in situations which there is no other possibility for funding (local authorities, private financial backing).

• Business and Industry:Local energy businesses, existing cooperative businesses or national energy companies. If there is an amount of superfluous energy it is possible to be sold to the national energy company.

2. Steps for a community to create an Energy Community project

2.1 Factors influencing the success of collective EC projects

Collective action, self-help, self-organising, these are some of the terms which can be used to describe the approach of community initiatives. Energy communities’initiatives require high levels of voluntary time and commitment. People’s motivation for becoming involved can also vary. It may be concern for one’s community or region, environmental concerns, or a sense of civic pride or engagement from people’s values and upbringing. Some or all of these motivations can bepart of your team. A number of key factors are required for successful energy communities’ initiatives:

Internal Factors

• Volunteer time / Volunteer skills

• Shared vision/consensus on projects

• Trust and support (among the group and with the community)

• Good Governance

External Factors

• Ability to access resources and create partnerships with statutory organisations: e.g. Development and Enterprise Support Organisations, Third Level Organisations, Municipalities

• Ability to access resources and create partnerships with other local bodies -e.g. civil society groups, sports groups etc

These supports can include capacity building resources (time and money), and capital support. While these supports may or may not be present, the real skill for community groups is to find out, approach, and win the support of the relevant decision-makers in the bodies and organisations who hold the keys to these resources.

Ripeness

Each community will have its own characteristics. In group projects, progress can seem slower than one might like. Thus, the importance of ‘ripeness’ -what projects are most likely to succeed given the available people and resources? It is important that your chosen project is within the capacity of the team that you have assembled. Or for example, there is no point pursuing a large wind project, if the community is divided about this technology. For projects to proceed, they must be able to use the resources that are available, both in the community and in the support environment.

Allow for Early Wins

While projects plans may be ambitious, projects which are to a high-level dependent on voluntary effort, should aim for a number of “early wins”. These are goals that can be achieved in the short to mid-term. The benefit of having “early wins”is that it gives a sense of satisfaction and achievement to the people involved andcan spur them on to further success.

Process and Pace

In all community initiatives, the “process” is important. One or two of the group may be very clear about the destination and may want to go ahead quickly. However, others may need to explore further, and ask more questions. This is a balancing act for any group. It is important tomove slow enough to ensure that everyone understands and feels able to contribute to the group decisions, and fast enough to keep people interested and motivated. One thinks of the Bruce Tuckman categories of the stages of group development “forming, storming, norming, and performing”.

Consensus Decision Making

Votes are to be avoided. Votes divide and separate people and are a sure way to create conflict. While it is not always possible to satisfy everybody, anchor the consensus principle into your work from the start, and allow enough time for discussion when taking decisions.

The challenge for energy community initiatives, is to cultivate and maintain a vision of what it wants, while dealing with the drudgery of slow-moving bureaucracies, planning, financial and other processes. It is precisely because there is a less than helpful and at times, oppositional state, that energy communities are required, to get things moving, to localise the benefits of the new energy economy.

2.2 The 4 steps for an energy community project

According to the project management principles there are 4 basic principles which must be followed up for a successful project implementation. The basic 4 steps are: Scoping, Planning, Doing and Reviewing

1st Step: Initiation and Scoping

• Identify initial area of interest (village, town, urban area, city). Decide what is the scale of the action.

• Identify assets and resources (potential partners, supporters, stakeholders)

• Meetings and group discussions (a community facilitator can be used if it is needed)

• Identification and decision making for the first project(s):

✓The options which should be picked have to be the most suitable related to the skills and resources which are available.

✓Prioritization of the potential project ideas based on some of the following factors: cost, timeframe, local value creation potential (jobs and investment), energy savings, revenue generation, fit with skills, values and goals of proposed team, availability of funding, timeframe & achievability (e.g. short, mid, long term), level of risk

• Decision making for the process of the project or not

2nd Step: Setup and Planning

• Commit to proceeding (Set up, elect the steering group. subcommittee with appropriate legal structure for the Energy Communities (L 4513/2018)

• Carry out further research into the area of opportunity –if it is required –for baseline data (this might include energy surveys)

• Agreement for the Project Scope. Focus on project design, business plan, costing, time involved, key milestones, technical requirements, grid or planning applications, assumptions, constraints, risks.

• Identification of specific funding opportunities –equity, share offering, social finance

• Meetings with project partners (e.g. local authority personnel, social finance,). Join with relevant local, regional and national support networks.

3rd Step: Doing

• Commence project (project management, project completion, regular project status updates to stakeholders to ensure ongoing oversight by group). Final work and contract closeout.

4th Step: Reviewing

• Review (lessons learned, identify areas for improvement, communication of the progress, engagement with the wider network, follow up opportunities)

2.3 Feasibility study for energy community

A co-operative is formed to serve its members by providing services that are used by the members.

It is critical to establish who will join the co-operative and actively use its services. The market issues revolve around questions such as:

– Can the co-op get better prices, better quality, or better services than potential members currently get through other means?

– How will the co-operative be, and remain competitive? Before spending a lot of time and money setting up a co-operative, be sure you can efficiently produce a product or deliver a service for a price people are willing to pay.

Depending on the size and complexity of the proposed co-operative venture, a feasibility study need not be elaborate and costly, but it must address the risks, benefits, strengths and weaknesses and answer the following questions:

– Concept: What product or service will you market?

– Market: Who is going to buy your product/service? Where?Why? And in what quantity? Who is your competition?

– Cost/Price: What will it cost to produce? What are people willing to pay? What is the competition charging?

– Production: How will your product be produced? How will thework be organized?

– Financing: How much will it cost to start-up? Where will the money come from? Member investment, banks or credit unions? How much will the co-op earn and when? While the feasibility study is not a substitute for a business plan, it must at leastprovide the basis for one.

Conducting a Feasibility Study:

Once a group of individuals has an idea for a renewable energy or energy efficiency project, they must evaluate whether or not it is feasible for them to do something about it. Evaluating the feasibility of aproject will likely include taking some of the following steps:

1. Define the intended benefits of the project for members and the community and characteristics (e.g. product and service discounts, improved salaries and working conditions, increased local employment,increased local control of energy production or usage, pollutionreduction, etc.)

2. Assess community receptiveness to the project

3. Identify and contact possible sources of technical, legal and financial assistance.

2.4 Developing the Business Plan

If your feasibility study returns a positive result, the next step is to develop a business plan. A business plan outlines the goals and objectives of the co-operative and the steps to reach those goals.

The business plan should be as complete as possible and include:

– The products or services that will be produced or sold (energy) to other similar products or services available on the market(quality and price),

– Equipment and material needed,

– The organization of work and the management approach,

– Financing requirements and the financing plan,

– List of external professional resources with whom the cooperative will work (accounting firms, legal firms, other cooperatives),

– List of legal requirements that must be complied with to operate thebusiness, and

– A timetable of activities

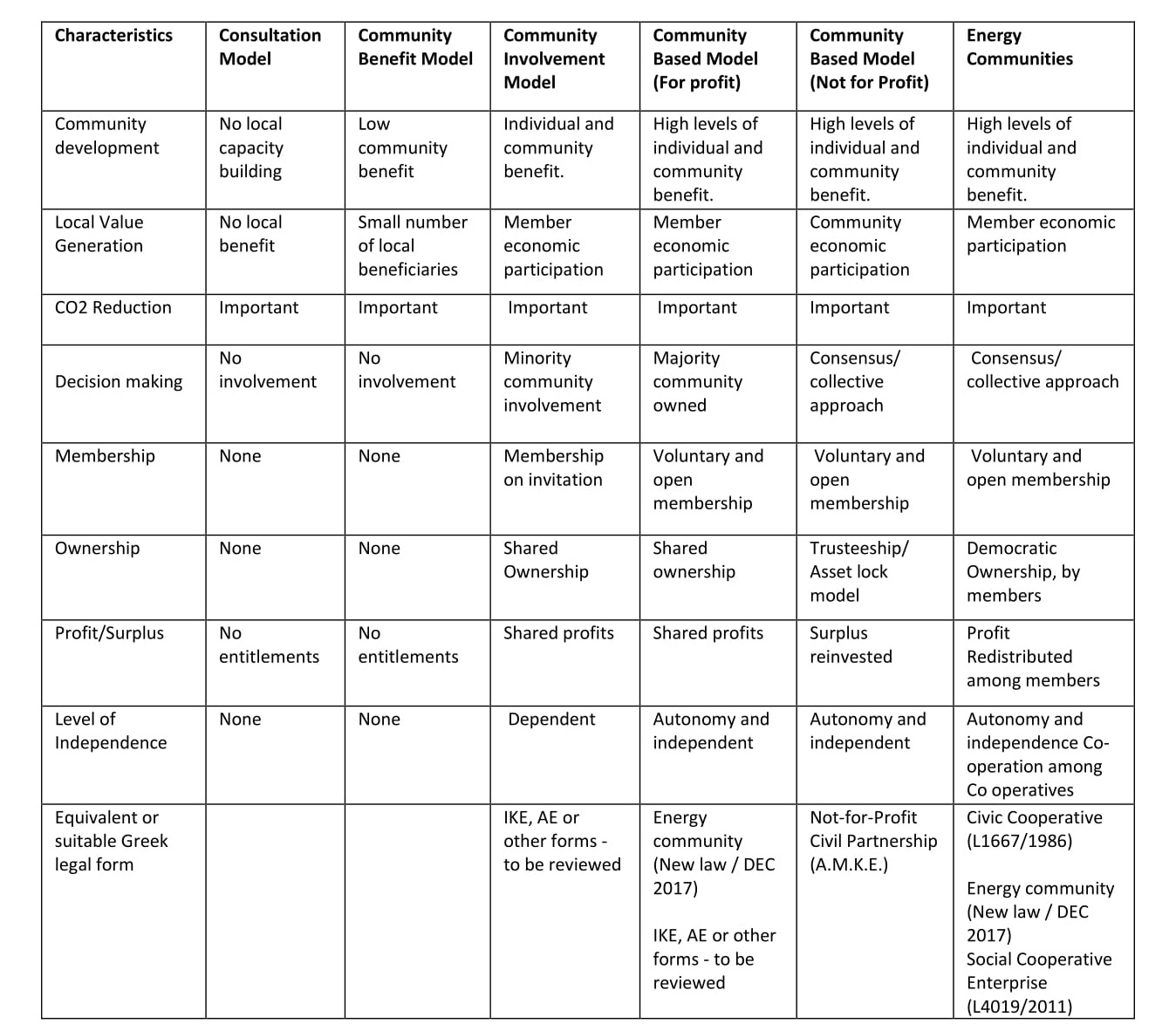

2.5 Energy community models

This section presents a scale of the different types of Energy community models, categorised according to several characteristics or ingredients. Different structures have these ingredients in different quantities. For example, cooperative energy structures differ fromstrictly charity or not-for-profit models, in being businesses with democratic ownership (decisions taken being based on equality among members, not shareholders). Coop structures can be more suitable for partnerships between individual citizens, local civil society actors, and local municipalities.

Consultations

Energy infrastructure projects, whether public or private, are usually carried out with consultations of one kind of another. Infrastructure consultations collect the views the people in the area near to or in some way affected by the project. While these consultations may shape aspects of the project, they do not give any financial benefit or direct influence in how decisions are made.

Community Benefit Models

Financial or other offerings are made to people or groups in the area near to or in some way affected by the project. This may be a one off or regular payment or other benefits, such as training opportunities, discounts on heating or energy bills. Where projects do not have the support of the local community, such compensations can be viewed negatively as trying to ‘buy off’ or even bribe a section of the community and can cause even deeper division. In some wind turbine developments, compensation can include a loss of value factor calculated for nearby householders.

Community Involvement Model

In this model, a part of the overall project is offered for investment to local stakeholders. In Denmark, up to 23% of wind projects must be offered to the local stakeholders. This requirement includes energy cooperatives which may include a number of local actors. This recognises the issue of social acceptance around some renewable technology.

Community-Based Model (for profit)

This model features a majority community shareholding which retains control interest in the project.

Community-Based Model (not for profit)

In this model, along with a majority community interest, profits are not distributed among members but re-invested back into the project.

Cooperative/Energy Community

Cooperatives have a number of agreed distinguishing features, the principal of which is one member one vote form of democratic ownership.Energy cooperatives can range from the 100% civil society owned, to platform coops where several stakeholders participate. In such cases, a project may be owned equally between civil society, municipal actors and private investors. For example, a Solar PV project on a local school, owned and run by a cooperative comprising of the school, the local municipality, and severalcivil society groups.

Characteristics of Energy Community Modules:

3. Steps to build an energy community in Greece

3.1 Current legal context in Greece and related basic information

Energy Communities are under the Greek National Law 4513/2018. The Energy Community is a fully-fledged urban cooperative with the aim of promoting social and solidarity-based economy and innovation in the energy sector, addressing energy poverty and promoting energy sustainability, production, storage, self-consumption, distribution and energy supply, enhancing energy self-sufficiency/security in island municipalities as well as improving energy efficiency in end-use at local and regional level.

Who can be part of an energy community?

• Individuals

• Public entities

• Legal persons under private law

• Local and regional authorities

What are the Locality criteria?

At least 51% of the members must be related to the place where the headquarters of the Energy Community is located. Specifically, the individuals must have full or minor ownership or usufruct on a property located within the region of the Energy Community or to be municipal residents of that region and the legal persons to have their headquarters in the region of the Energy Community.

3.2 Local energy ownership model of Greece

The structure of the support regime for renewable electricity in Greece has changed. In January 2018, a new law on energy communities was voted in the Greek Parliament, which defines the role of citizens in the energy sector and gives wide scope for energy communities. The law encourages citizens, local authorities and private and public agencies to participate in the production, distribution and supply of energy; essentially, it gives electricity consumers a possibility to become electricity producers. The main driver for reform is to bring Greece into compliance with the European Commission’s Guidelines on State aid for environmental protection and energy for the period 2014–2020 (Guidelines).

According to press coverage, the changes enable energy communities to produce, sell or self-consume electricity and thermal energy produced by RES or CHP. The law enables local energy communities to set-up ownership structures and prohibits the charging of fees to renewable energy communities that do not align with real costs. Overall, the objective of the law is to enable citizens, municipalities and regions to directly participate in energy projects, particularly renewable energy projects. It also aims to ensure energy communityprojects do happen in the community by laying down requirements for the member of the community to be linked to the place of its headquarters.

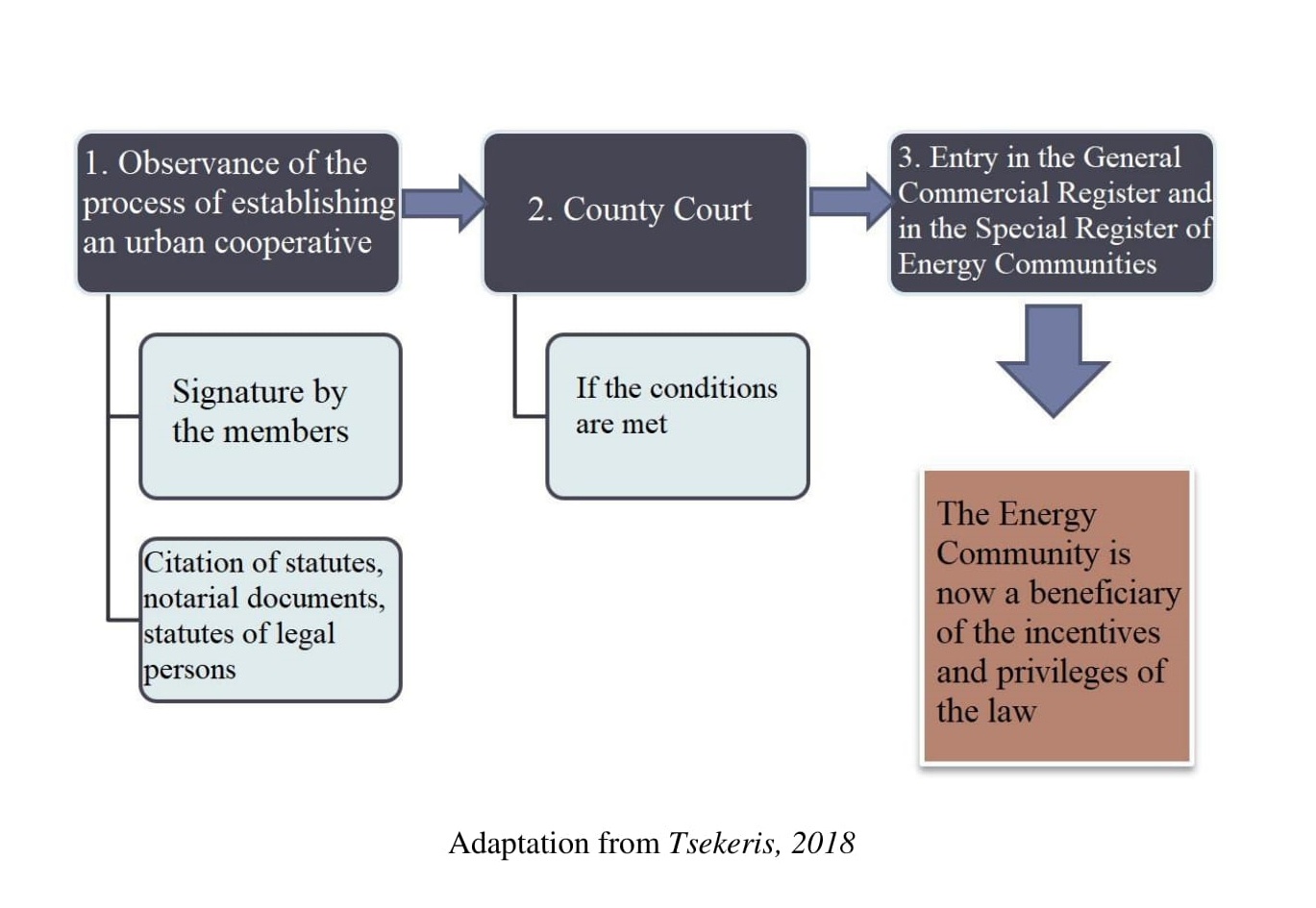

3.3 The process of setting up an energy community in Greece

Below it is presented a scheme in which you can understand the specific steps which have to be followed during the process of setting up an energy community in Greece (Tsekeris, 2018).

The process for the establishment of an Energy Community must follow the establishment process of an urban cooperative. The statutes must be signed by the members.

The following supporting documents shall be presented to the County Court:

✓The statute of the Energy Community

✓Notarial documents or real estate statements for individuals proving the full or fine ownership or usufruct of a property in the Region of the registered office of the Energy Community or the certificates of marital status of individuals-members who are citizens of the municipality of the Region in which the Energy Community is located

✓The statutes of the legal persons –members of the Energy Community

The Energy Community acquires legal status after the registration of its statues to the General Commercial Register and in the Special Register of Energy Communities.

3.4 Formation of an Energy Community

In this section are presented some important information about the difference between the profitable or not character of the energy communities, the options related to the minimum number of members and some other critical information (e.g. exceptions about Island areas) (Tsekeris, 2018).

Non-Profit Character (no redistribution of surplus use possible)

Minimum members’ number

1. Five (5) if the members are individuals or public entities (5*20%)

2. Three (3) if the members are only local or regional authorities(e.g.35%, 35%, 30%)

3. Three (3) if the members are individuals, or public entities or legal persons under private law of which two (2) of them must be local or regional authorities(20%, 40%, 40%)

4. Two (2) if the members are local or regional authorities located in an island area(50%, 50%)

Profit distribution

– Profit distribution is not allowed -Reserve and disposal for the purposes of E.C.

– An exception for the islands (<3100), a portion of the profits may be allocated to local utility actions (e.g.tanks etc.)

Profitable Character (distribution of surplus usage)

Minimum members’ number

– Fifteen (15) if the members are public entities or legal persons under private law or individuals

– Ten (10) if the Energy Community is in an Island municipality.

– Fifty percent (50%) plus one (1) must be individuals (profit distribution is allowed)

Profit distribution

– Thedistribution ofthe balance of net profitsis allowedafter deduction of reserves to members.

General Information

– Each member has one vote, irrespective of the cooperative capital it owns.

– The “speculative” or “non-profit” character of E.C. remains throughout its life.

– Cooperative portions: Each member may hold, in addition to the compulsory cooperative share and one or more optional cooperative shares, with a maximum of 20% in the cooperative capitale xcept for the local or regional authorities who may participate in cooperative capital up to a maximum of 40%.

– Special term for Islands: for islands with <3100 inhabitants, the participation rates of local or regional authorities can reach 50%.

3.5 Activities of an Energy Community

An Energy Community must carry out one of the following activities(Tsekeris, 2018):

– Production, storage, own consumption or sale of electric or thermal or cooling energy from RES stations and for High Efficiency Co-generation of Heat and Power established within the Region where the Energy Community is located

– Managing (collecting, transporting, processing, storing, supplying) raw material to produce electric or thermal or cooling energy from biomass or bioliquids or biogas or through the energy recovery of the biodegradable fraction of municipal waste

– Supply to the members: energy products, appliances, installations to reduce energy consumption and use of conventional fuels, and improvement of the energy efficiency.

– Supply to the members:electric vehicles (hybrid or non-hybrid) and vehicles which usenatural gas, liquefied petroleum gas or biogas.

– Distribution of electricity within the region of its headquarters or distribution of thermal or cooling energy.

– Supply of electricity or gas to Final Customers within the region where its headquarters are located.

– Demand management to reduce end use of electricity

– Development, management and exploitation of the charging stations for electric vehicles (CNG, LNG, LPG or biogas) or the management of sustainable transport means within the region of the Energy Community.

– Installation and operation of water desalination units using RES

– Provision of Energy Services (ESCOs)

Also, an Energy Community can potentially carry out the following actions(Tsekeris, 2018):

– Attracting funds for investments in the field of the exploitation of RES or High Efficiency Co-generation of Heat and Power or interventions to improve energy efficiency within the regional unit where the Energy Community is located.

– Preparation of technical and economic studies for the exploitation of RES or High Efficiency Co-generation of Heat and Poweror the implementation of energy efficiency improvement interventions or the provision of technical support to the above sectors.

– Managing or participating in programs funded by national or European Union resources for its purposes.

– Provide advice on the management or participation of its members in programs funded by national or European Union resources for its purposes.

– Information, education and awareness at local and regional level on energy sustainability issues.

– Actions to address energy poverty for vulnerable consumers or people below the poverty threshold, regardless of whether they are members of the energy community, such as indicatively providing or offsetting energy, energy upgrading housing or other measures that reduce energy consumption in citizens’ homes.

✓ The statute of an Energy Community does not include other activities than those mentioned.

3.6 Financial Incentives & Support Measures

What are the financial incentives and support measures for an Energy Community in Greece?(Tsekeris, 2018)

– Integration of the Energy Communities to the Development Law (Law 4399/2016)-by analogy with the Social Cooperative Enterprises-as well as other programs funded by national or European Union resources.

– Possibility for special conditions and terms of preferential participation or exclusion from competitive bidding procedures (MOUs) and preferential charges for market services

– Exemption from the obligation to pay the annual fee for holding an electricity generation license

– Priority to grant production license, connection offer, and approval of environmental conditions for power stations (if they have aterritorial overlap and are subject to the same application cycle)

– Reduced Letters of Guarantee (50%)

– The installation of photovoltaic stations and small wind turbine stations is allowed for the Energy Communities in order to meet the energy needs of their members using a virtual energy netting (also for non-members).

– Transfer of licenses, production plants exclusively to Energy Communities, with a similar allowable way of allocating surpluses for use within the same region.

Πηγή: info-pack-establishment-of-energy-community. (website: https://enercommunities.eu).